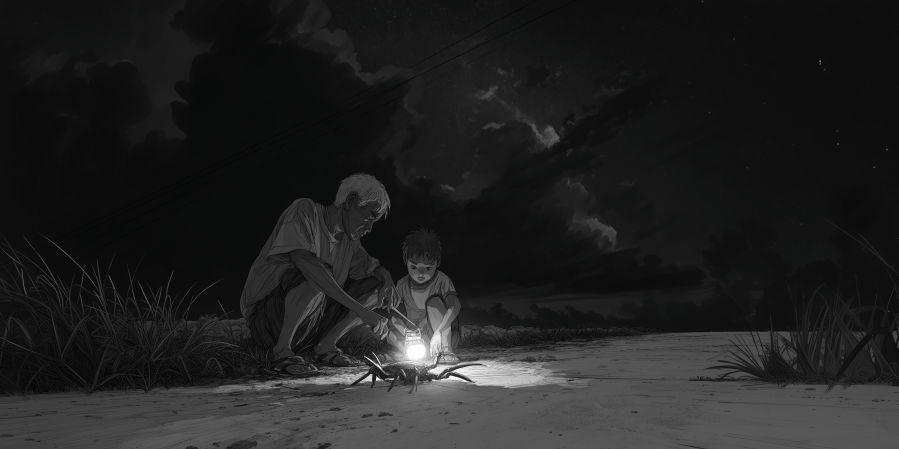

The next story for our Saturday practice group is about a father and son, providing a warm narrative that frames the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next. This will be one of the longer pieces that we’ve used for our group, and for good reason: we get to see both a small slice of the life led by the father-son pair as well as several sets of instructions that detail the fabrication and use of various types of traps and other implements for gathering crabs under different conditions. And on a more personal note, our friend Dabit will be facilitating several Saturday practice sessions in our stead while we take some time for a loss in our family.

As ever, in this post you’ll find the Chamorro text, an English translation, and an audio narration by Jay Che’le. Footnotes to follow. Happy reading!

Umépanglao

Tinige’ as Jesus C. Barcinas

Pinenta as Rogelio G. Faustino

Un dia, åntes ha’ di u tunok i atdao, humånao si Tony yan si tatå-ña para i lanchon-ñiha para u na’chochu i mannok siha. I tatan Tony sumóso’su’ i niyok siha gi empi’ pontan. Si Tony ngumångangas i sine’su’ niyok siha pues ha yóyotte i mannok ni’ bagåsu.

Ilek-ña si Tony as tatå-ña, “Nihi, Tåta, ya ta fanina pånglao lámo’na sa’ hinekkok i pilan. Siempre mehna hit pånglao.”

“Maolek ha’ nai, Tony, sa’ gos malago’ yu’ chumochu kåddun pånglao,” ilek-ña si Tåta.

“Guahu lokkue’,” ilek-ña si Tony. “Esta hu chagi i flashlight ya gos ma’lak. Esta lokkue’ hu na’listo i kestat ganggoche.”

“O, pues hagas ha’ gaige gi hinasso-mu na para ta fanina pånglao, no?” finaisen as tatå-ña.

“Si, Señot,” manoppe si Tony.

“Maolek nai,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña. “Maolek ta chagi, ya siña ha’ guaha suette-ta.”

Si Tony fine’nana kumuentos, “Taya’ todabia pånglao humuyong gi ngilo’-ña.”

“Munga inalula, låhi-hu. Ti apmam mangonne’ hit,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña. “Ayugue’ un pånglao na umá’apu’ gi achu’,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña.

“Baba i kestat pues atan håfa taimanu konne’-hu ni’ panglao. Bai honñu’ i panglao ni’ patman kannai-hu kontra i tanu’. Bai na’mafñot honño’-hu ya cha’ña u kalálamten i panglao. Bai mantiene mafñónot lokkue’ i ocho na kalulót-ña i panglao. Pues bai sahguan gi halom i kestat.”

Esta monhåyan makonne’ i un pånglao. Sigi mo’na si Tony yan si tatå-ña gi kanton tåsi. Sigi di ha ina i papa’ tronkon gågu yan i halom håli’ siha gi kantun tåsi. Meggai na pånglao ha líli’e’ i dos ya gof nina’emperao si Tony.

“Ayugue’ dos gi papa’ håli’,” umessalao si Tony. “Ayugue’ ta’lo tres gi papa’ i hagassas. Láchaddek kumonne’, Tåta, sa’ u fanhålom gi maddok-ñiha.”

“Ékahat ha’ i pachot-mu, Tony,” sinangani si Tony as tatå-ña, “ya baba i kestat. Ti u fanhålom gi maddok i panglao siha sa’ manmañå’ot.”

Sigi di ha konne’ i tata i panglao siha ya ha sahguan gi halom i kestat. Annai esta para lamitå sinahguan-ña i kestat ni’ hinan-ñiha, ilek-ña si Tåta ni’ lahi-ña, “Tony, hågu på’gu un sahguan i panglao siha gi halom i keståt-ta. Siña mohon un cho’gue?”

“Ai! Ha akka’ yu’ i panglao!” umessalao si Tony.

“Honñu’ påpa’ i tatalu’ i panglao. Na’duru. Na’setbe todu i dos kannai-mu,” tinago’ si Tony as tatå-ña.

“Tåta, gos puti i kannai-hu sa’ chéchetton ha’ i panglao gi kalulot-hu,” ilek-ña si Tony.

“Nangga nai ya bai hu iteng i dáma’gas i panglao ni’ umá’akka’ kalulot-mu,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña. “Esta må’teng på’go.”

“Tåta,” ilek-ña ta’lo si Tony, “lao chéchetton ha’ i dáma’gas i panglao gi kalulot-hu. Dia’.”

Ha åkka’ i tatan Tony i dáma’gas i panglao, ya sinetta si Tony. Gos puti i kannai-ña lao ha sungon låhi ha’. Åhe’, ti tumånges si Tony.

“Chagi fan ta’lo mangonni’ otru na pånglao ya un sahguan gi kestat,” tinagu’ ta’lu si Tony as tatå-ña.

På’gu na biahi ha gos adahi gue’ si Tony. Ha baba i dos kannai-ña, ha honñu’ påpa’ dúruru i tatalo’ i panglao, ya ha mantiene todu i ochu na kálulot i panglao siha. Pues ilek-ña gi panglao, “Toka hao, no!” Ya ha sahguan i panglao gi halom i kestat.

“Taiguenao nai, låhi-hu,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña. “Esta siña hao umépanglao på’gu. Un na’gos magof yu’.”

Mangonne’ si Tony sais ta’lu na pånglao ya ha sahguan gi halom i kestat. Ilek-ña ta’lu si tatå-ña, “Båsta på’gu, Tony, sa’ esta meggai na pånglao gi halom i kestat, ya duru siha maná’akka’. Esta mana’na’getmun. Lao dipotsi ha’.”

“Buente esta meggai na pånglao manmåtai,” ilek-ña si Tony as tatå-ña.

llek-ña si tatå-ña, “Maila’ ya bai hu fa’nu’i hao håfa taimanu para ti u fanápuno’ i panglao siha. Go’ti i kestat, na’mafñot kontra i panglao siha. Pues chuli’ i godde-mu ya un godden mafñot i kestat.”

Mangeto i panglao siha annai esta monhåyan magodden mafñot i kestat lao pues duru di mambesbes. “Un li’e’, Tony?” ilek-ña ta’lu si tatå-ña. “Yanggen magodden mafñot i kestat ti siña mangalamten i panglao siha pues ti siña maná’akka.

“Esta hu komprende, Tåta,” ilek-ña si Tony.

Annai esta gos mehna si Tony yan tatå-ña pånglao, humånao i dos para iya siha. “Basiha i panglao guatu gi halom tångken dånkulu,” tinagu’ si Tony as tatå-ña annai måttu i dos gi gima’. Ha chuli’ si Tony i kestat pånglao ya ha basiha i panglao siha guatu gi halom tångken dånkulu. Duru i panglao siha manmumu ta’lu. Ti apmam måttu tåtti si tatå-ña yan un manohu na hagon chotda ni’ mambébetde ha’.

“Para håfa enao, Tåta?” si Tony ha faisen si tatå-ña.

“Para u nina’fangeto i panglao siha, Tony,” manoppi si tatå-ña. “Atan ha’.” I tatan Tony ha sohmuki i tanke ni’ hagon chotda siha. Mangeto ta’lu i panglao siha.

“Magåhet, Tåta, na mangeto,” ilek-ña ta’lu si Tony. “Kao siña i hagon chotda makånno’ ni’ panglao?” “Hunggan, siña makånno’ i hagon chotda,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña.

Ha faisen si tatå-ña ta’lo, “Siña mohon, Tåta, un sangåni yu’ mas pot pånglao?”

Ineppe as tatå-ña, “Sa’ håfa na ti u siña? Lao po’lu esta agupa’. Guaha siha para ta cho’gue på’gu.”

Gi sigiente dia annai gaige i dos gi kusina, sinangåni si Tony as tatå-ña otro siha na estoria pot pånglao.

“Tony,” ha tutuhon si tatå-ña, “åntes na tiempo masusulo’ i panglao yanggen homhom esta. Hachón ma’u’usa ni’ taotao siha yanggen mañulo’. Yanggen para un fama’hachón, un nisisita i anglo’ na hagåssas. Na’suha i ba’yak i hagåssas, masea hulok pat utot. Yanggen esta un hulok pat un utot i ba’yak, tutuhon fumuñot i hagåssas ginen i yapåpapa’. Fuñot ya un godde i hagåssas ni’ mismo hagon-ña. Godde kada dos kuattas estaki matto gi puntan i hagåssas. Songge i hachón ya un ina i panglao sa’ siempre un li’e’ taiguihi ha’ yanggen un usa i flashlight.

Guaha ta’lo otro na klasen umepånglao. Este i maguålaf i pånglao. Yanggen gualaffon i pilan, manmañå’ot i pånglao. Siña un konne’ pånglao sa’ ini’ina ni’ pilan, lao mas maolek yanggen ma’ina ni’ hachón.

“Siña lokkue’ makonne’ i pånglao gi umechenglon. Gigon kahulo’ i atdao, guaha siha pånglao ni’ manabak ya mañenglon gi hale’ tronko pat mannatata na ngulo’ nai manhalom. Yanggen taftaf guatu gi sagan pånglao i ume’epånglao, siña ha’ mangonne’.

“Makókonne’ ha’ lokkue’ i pånglao ni’ desguas. Chule’ un tangantångan ni’ ñahlalang. Maolek i sais pie na inanakko’. Fama’tinas låsu ni’ kotdet ya un godde gi puntan i pisao tangantangan. Kahulo’ gi un ramas tronkon hayu annai siña hao mata’chong ya un hago’ lumåsu i dáma’gas i pånglao yanggen humuyong gi maddok-ña.

“Siña ha’ lokkue’ makonne’ i pånglao ni’ ekkodo. Pi’ao mafa’o’okkodo. Utot i pi’ao gi kada gåhu. Po’lo ha’ un punta gi gahu na u machom (C) ya i otro punta u mababa (A) para pachot i ekkodo (I). Gi talo’ i machom na puntan i gahu (C) dulok ni’ se’se’ un maddok dikike’ para u siña humålom i manana gi halom i bengbong. Dos potgådas desde i pachot i bengbong måtka (B). Gi (B) dulok dos maddok dikike’ para u siña humålom i alåmle (2).

“Chåchaki låta para un godde gi pachot i ekkodo. Na’mås dikike’ i chinachak låta ki i maddok i pachot i bengbong para u siña u hålom i manana gi halom i bengbong (3). Presisu na u manana i halom i ekkodo sa’ hinasso-ña siempre i pånglao na i pachot i maddok-ña i maddok gi gahu. Dulok dos na måddok dikike’ gi chinachak låta para u siña mana’halom i alåmle. Na’hålom i låta gi pachot gåhu pues na’hålom i alåmle ni’ gaige gi låta gi dos måddok dikike’ gi gahu (B). Godde i alåmle (4). Na’ kållo i ginedden alåmle para u siña humålom i panglao lao ti siña ha bira gue’ papa’ gi maddok. Na’talak papa’ i pachot i ekkodo gi ngilo’ pånglao ya un plånta na’fitme.

“Guaha otro na klasen okkodon. Este i okkodon åtkus. Para un fa’tinas este na okkodo, un nisisita este siha na matiriåt:

- un gåhu gi pi’ao loddo’ ni’ måchom un punta ya mababa i otro punta (i pachot)

- un linasguen pi’ao ni’ acha’anåkko’ yan i gahu ya media potgåda inancho-ña, yan un pidason hahlon ni’ kuatro potgådas inanakko’-ña

- un linasguen pi’ao ni’ acha’anakko’ yan i gahu ya un potgåda inancho-ña, yan un pidåson hahlon ni’ lamitå i inanakko’ i linasguen pi’ao

- un ganchon dikike’ ni’ machåchak ginen i pi’ao

- un kalåktos na se’se

“Este siha un cho’gue:

- Gi talo’ i machom na puntan i gahu (bongbong) dulok ni’ se’si’ un måddok dikike’ para u siña humålom i manana gi halom bongbong (1).

- Chule’ i ládalalai na linasguen pi’ao ya un godde i un punta ni un puntan i hahlon. Cho’gue taiguini ta’lo gi otro puntan i linasgue (2).

- Chule’ i láfedda’ na linasguen pi’ao ya un måtka i talo’. Desde este na måtka, gi santatten i linasguen pi’ao, lasgue na’potpot i pi’ao un potgåda. Munga matugan este na sinifan sa’ para chiget este. Desde i talo’ i linasguen pi’ao ta’lo, sufan ya u láladalalai esta akadidok i otro punta (3). Godde este na punta ni’ otro pidåson hahlon. Godde lokkue’ i ganchon pi’ao gi otru puntan i hahlon.

- Fanråya na’tunas gi bengbong desde i un punta esta i otro punta. Dos pat tres potgådas desde i pachot, matka (A) gi råya. Måtka lokkue’ (B) gi mina’sinko potgådas desde i pachot i bengbong. Gi otro puntan i bengbong måtka (C) gi råya gi mina’dos pat tres potgådas ginen este na punta (4).

- Gi (A) dulok ni’ se’se’ na’atrabisao kontra i råya, un måddok ni’ dos potgådas inanakko’-ña ya media potgåda finedda’-ña (1).

Gi (B) råya un potgåda, na’atrabisao lokkue’. Sufan na’potpot i lassas i pi’ao un potgada na inancho desde (A) estaki måtto guatu gi (B). Munga matugan este na sinifan sa’ para chiget este.

Gi (C) dulok un måddok dikike’ para siña u gini’ot i gancho ni’ para u talak hålom påpa’ gi bengbong. - Chule’ pa’go i linasguen pi’ao ni’ magógodde dos punta. Mantiene i talo’ ya chiget halom gi sinifan gi lassas entre i (A) yan i (B). Na’mafñot ya u chetton. Munga machiget i hahlon (2).

- Chule’ i otro na linasguen pi’ao ya un na’hålom i fedda’ na punta gi maddok (A). Na’siguru na siña humulo’ påpa’ i linasgue gi maddok. Chiget i hahlon i dalalai na linasguen pi’ao gi sinifan para chiget gi láfedda’ na linasguen pi’ao. Na’tohge i fedda’ na linasguen pi’ao gi kånto ha’ guini gi maddok (A), pues estira i dalalai na punta ni’ gai gancho. Na’saga i gancho gi maddok dikike’ (C) ni’ gaige gi otro puntan i bengbong (3).

- I gancho debi di u talak guatu gi pachot bengbong. Debi lokkue’ i gancho na u siña humulo’ papa’ gi maddok, lao pega ya u estirante i hahlon yan i pi’ao ni’ mumantiétiene. Debi di u fama’åtkos todu i dos. Esta kabåles i ekkodo (4).

“Na’talak papa’ i pachot i ekkodo gi ngilo’ pånglao ya un plånta na’fitme. Yanggen guaha pånglao gi ngilo’ siempre u malago’ humuyong. Siempre u hålom gi ekkodo para u falågue i manana gi punta. Åntes di u sen fåtto gi punta siempre u totpe i gancho. U pechao hulo’ i gancho, ya gi mismo tiempo tumachu hulo’ i sumustiétiene na linasguen pi’ao gi maddok (A). Siempre sulon påpa’ este na linasgue gi halom bongbong ya ha trangka i pachot i ekkodo. Chenglon i pånglao gi sanhalom estaki guaha matto para u kinenne’.

“Guaha otro klasi na okkodo lokkue’, i ekkodon låta. Para este na okkodo, nisisita na un guaddok i tano’ para u ulat i låtan pitrolio. Håfot i låta. Debi di u talak hilo’ i pachot i låta. Na’siguru na umalapåt i pachot i låta yan i edda’. Nå’ye katnåda i fondon i låta. Bagåson niyok yan mahek lemmai maolek na katnåda. Siempre mamoddong i panglao gi halom i låta ya ti u fangahulo’.

“Este ha’ hu tungo’ pot umepånglao, lahi-hu. Siña ha’ lokkue’ mamaisen hao gi pumalon manatungo’-ta yanggen malago’ hao un tungo’ mas pot umepånglao. Guaha na taotao mas manabet ya manggai åtte para u fanlibianu manepånglao. Gof magof yu’, Tony, sa’ interesao hao na un tungo’ pot umepånglao. Bentåha para hågu este siha na tiningo’,” sinangåni si Tony as tatå-ña.

“Gof magof yu’ lokkue’, Tåta, sa’ siña yu’ manungo’ ginen hågu. Si Yu’us ma’åse’ pot i maolek na ehemplo ni’ un sangåni yu’. Esta på’go siña yo umepånglao na maisa ya ti u åkka’ yu’ ese daddao,” ilek-ña si Tony.

“Taiguenao nai, lahi-hu. Cha’mo ma’å’ñao ni’ pånglao,” ilek-ña si tatå-ña.

Searching for Crabs

Written by Jesus C. Barcinas

Illustrated by Rogelio G. Faustino

One day, just before the sun set, Tony and his father went to their ranch to feed the chickens. Tony’s father scooped the coconut meat from a split sprouting coconut. Tony was chewing t he meat and throwing the dried meal to the chickens.

Tony said to his father, “Let’s go, dad, and shine crabs tonight, since the moon is new. Surely we’ll have a plentiful catch of crabs.

“Sounds good, Tony, because I really want to eat crab soup, said Dad.

“Me too,” said Tony. “I’ve already checked the flashlight and it’s very bright. I’ve also readied the (burlap) sack”

“Oh, so you’ve been thinking about us shining crabs, huh?” asked his father.

“Yes sir,” answered Tony

“well good” said his father. “It’s good for us to give it a try, and maybe we’ll be lucky.

Tony was the first to speak, “There aren’t any crabs that have come out of their holes yet.”

“Don’t rush, son. We’ll catch soon,” said his father

“There’s a crab leaning on a rock,” his father said. “ Open the bag and look at how I catch the crab. I’ll pin it against the ground with my palm. I’ll pin it tightly and the crab won’t be able to move. I’ll also tightly grip the crab’s eight legs. Then I’ll put it in the bag.

He had already caught a crab. Tony and his father continued on a the edge of the ocean. He kept shining light on the bottoms of Ironwood trees and into the roots on the beach. The two saw many crabs and tony was very excited.

“there’s two under the roots,” shouted Tony. “There are three others in the dead leaves. Hurry up and catch them, Dad, because they’ll go into their holes.

“soften your voice, Tony,” his father said to him, “ and open the bag. The crabs won’t go into the holes because they are ready to lay eggs.” The father continued collecting crabs and put them in the bag. When the sack was nearly half full with their catch, Dad said to his son, “Tony, you’re going to put the crabs in the bag. Do you think you can do it?”

“Ah! The crab pinched me!” Tony shouted.

“Press down on the crab’s back. Make it hard. Use both your hands,” his father directed him.

“Dad, my hand really hurts because the crab is still stuck to my finger,” Tony said.

“Well, wait and I’ll break off the crab claw that’s pinching your finger.” His dad said. “it’s fallen off now”

“Dad,” Tony said again “but the crab claw is still stuck to my finger. Look.”

Tony’s dad bit the crab claw and Tony was released. His hand really hurt, but he simply braved the pain. No, Tony didn’t cry.

“Try again to catch another crab and put it in the sack,” Tony’s father instructed him.

This time, Tony was very careful, and he held all eight legs of the crab. Then he said to the crab “you’re in trouble, huh?” And he placed the crab into the sack.

“Just like that, my boy,” said his father. “Now you can gather crabs. You’ve made me so happy.”

Tony caught another six crabs and put them into the sack. His father said again, “that’s enough for now, Tony, because there are already so many crabs in the sack, and they keep pinching each other. They’re already getting turned to gristle. But it should be that way.”

“A lot of the crabs have probably died,” said Tony to his father.

His father said, “Come and I’ll show you how to prevent the crabs from killing each other. Hold the sack, make it tight against the crabs. Then take your rope and tie the sack tightly.” The crabs were still once the sack was tied tight but then they kept swishing around. “you see, Tony?” his father said again. If the sack is tied tightly, the crabs can’t move and so they can’t pinch one another.”

“I understand now, Dad,” Tony said.

When Tony and his father had a plentiful catch of crab, the two went home. “Pour the crabs out into the big drum,” Tony’s father instructed him as they got to their house. Tony took the sack of crabs and poured them out into the large drum. The crabs kept fighting again. Soon his father returned with a bundle of banana leaves that were still green.

“What’s that for, Dad?” Tony asked his father.

“To keep the crabs still, Tony,” his father answered

“just watch.” Tony’s dad stuffed the drum with the banana leaves. The crabs were still again.

“They really did keep still, Dad,” Tony said. “Can the banana leaf be eaten by the crabs?”

“Yes, the banana leaf is edible,” his father said.

Tony asked his father again, “could you tell me more about crabs, dad?”

His father answered, “Why wouldn’t I? But leave it until tomorrow. We have things to do today.”

The next day, when the two were in the kitchen, Tony’s father told him another story about crabs.

“Tony,” his father began, “back in the day, the crabs would come out when it was dark. People would use torches when they came out. In order make a torch, you need dry dead coconut leaves. Get rid of the stem from the leaves, either break it off or cut it. When you’ve already broken off or cut the stem, start bundling the leaves from the very bottom. Bundle and tie the leaves with themselves. Tie every other hand’s length until you get to the tip of the leaf. Burn the torch and you can shine the crabs because surely you’ll see just as though you were using a flashlight.

“There’s another kind of crab-gathering. This is maguålaf. When the moon is full, the crabs are ready to lay eggs. You can catch crabs because the moon is shining them, but it’s better when you’re shining with a torch.

“You can also catch crabs when they’re encumbered. As soon as the sun rises, there are crabs that are lost and entangled in the roots of trees or shallow holes that they’ve gone in. If you’re get to the crabbing place early, you can catch them”

Crabs are also caught with the desguas. Take a tangantangan that’s thin. Six inches is a good length. Make a lasso with the cord and tie it to the tip of the tangantangan pole. Get up on the branch of a tree where you can sit and reach to lasso the claw of the crab when it comes out from its hole.

“You can also catch crabs with a trap. Bamboo is made into traps. Cut the bamboo at each joint/segment. Leave one end with the joint closed, and the other will be open to serve as the mouth of the trap. In the middle of the closed end, poke with a knife and make a small hole so that the light can come into the segment (hollow). Make a mark two inches from the mouth of the trap. Here, poke two small holes so that the wire can go in.

“Cut a can to be tied to the mouth of the trap. Make the cut can smaller than the hole so that the light can go into the hollow. It’s critical that the trap get light inside, because the crab will then think that the hole in the joint is the mouth of its hole. Poke two small holes in the cut can to put the wire through. Put the can into the mouth of the segment And then insert the wire from the can into the two small holes on the segment. Tie the wire. Tie the wire loosely so that the crab can go in but can’t turn back to its hole. Face the mouth of the trap to the hole of the crab and set it securely.

“There’s another kind of trap. This is the Arch Trap. In order to make this trap, you need these materials:

- A segment of bamboo with a closed end and an open one (the mouth)

- A sliver of bamboo that’s the same length as the segment and is half an inch thick, and a piece of string that’s four inches long

- A sliver of bamboo that’s the same length as the segment and is an inch thick, and a piece of string that’s half as long as the bamboo

- A small trigger/latch that’s cut from the bamboo

- A sharp knife

“This is what you do:

- In the middle of the closed end of the segment (hollow) poke a small hole with a knife so that the light can enter the hollow

- Take the thinner strip of bamboo and tie one end with the end of the string. Do the same to the other end of the strip.

- Take the thicker strip of bamboo and mark its midpoint. From this mark, at the back of the strip, split a strip one inch wide. Don’t break off this split part because it’s for a clip. From the middle of the strip again, whiddle to narrow the end to a sharp point. Tie this point with the other piece of string. Tie the trigger/latch to the other end of the string.

- Make a straight line along the hollow from one end to the other. About two or three inches from the mouth, make a mark on the line (A). Mark again at five inches from the mouth (B). At the other end of the hollow, make a mark on the line at about two or three inches from the end (C).

- At mark (A), poke a hole about two inches long and half an inch wide with the knife perpendicular to the line. At mark (B), draw a one-inch line, perpendicular as well (to the main line). Split a thick section of bamboo one inch wide from (A) until it reaches (B). Don’t break off this split part because it’s for a clip. At mark (C), poke a small hole so that the trigger/latch can be held facing it at the bottom of the hollow.

- Now, take the strip of bamboo that is tied on both ends. Hold the middle and pinch it in the split of bamboo skin between (A) and (B). Make it tight so that it stays. Don’t pinch the string (2).

- Take the other strip of bamboo and insert the thicker end in the hole at (A). Ensure that strip is able to move up and down within the hole. Pinch the string of the thin strip in the split part of the thicker strip, which was intended to be a clip. Stand the thicker strip on the edge of the hole at (A), then stretch the narrower end which has the trigger/latch. Secure the trigger/latch in the small hole at (C), which is at the opposite end of the hollow (3).

- The trigger/latch should face the mouth of the hollow. It should also be able to move up and down in the hole, but place it so that the string and the bamboo that it’s holding are stretched. The two should form an arch. The trap is now complete (4).

“Face the mouth of the trap down to the crab’s hole and place it securely. If there’s a crab in the hole, it’ll want to come out. It will then enter the trap to run to the light at the far end. Before it fully reaches the end, it’ll hit the trigger. The trigger/latch will quickly shoot up and at the same time, the strip of bamboo supporting it will stand at the hole. The strip of bamboo will slide down into the hollow and will gate the mouth of the trap. The crab is trapped inside until someone comes to harvest it.

“There’s another type of trap too, the can trap. For this trap, you need to dig the earth in order to fit a kerosene can. Bury the can. The mouth of the can should be facing upward. Ensure that the mouth of the can is side-by-side with the dirt. Place bate at the bottom of the can. Ground coconut and spoiled breadfruit are good bait. The crabs will fall into the can and won’t climb out.

“This is all I know about harvesting crabs, my boy. You can also ask amongst the people we know if you want to learn more about harvesting crabs. There are people who are mor knowledgeable and have tricks to make crab harvesting easy. I’m so happy, Tony, that you’re interested in learning about harvesting crabs. This knowledge is an advantage for you.” Tony’s father told him.

“I’m very happy too, dad, because I can learn from you. Thank you for the good examples that you’ve told me about. I can now gather crabs on my own and that aggressive one won’t pinch me,” Tony said.

“That’s the way it is, son, don’t be afraid of the crab,” his father said.

Notes

Source

Jesus C. Barcinas, “Umepanglao,” University of Guam Digital Archives and Exhibitions, accessed November 18, 2025, https://uogguafak.omeka.net/files/show/1053.