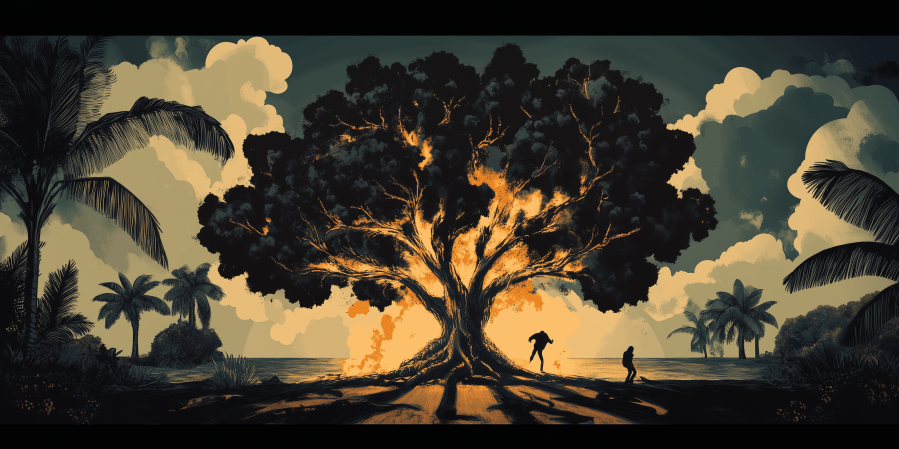

Our story for this Saturday’s practice group is this fantasy short story written by Jay Che’le, edited by Ray Barcinas and friends. In this story, we follow the fictional main character Chå’ as they recount a dramatic encounter with taotaomo’na in Talaifak (a historic Chamorro village on the southen end of modern-day Hågat/Agat on Guam). This story draws inspiration from different encounters with taotaomo’na that happened in Jay’s family in Talaifak over the years, some of which still give everyone goosebumps when they recall them. These encounters range from people suffering a sleepless night, to a dramatic instance when a mango tree was burned to expel the ill-intentioned taotaomo’na (who were in the tree) to the islet of Annai. This explusion of these spirits is why Jay’s mother always told him to never go to Annai.

This post includes the Chamorro text, English translation, and an audio narration in Chamorro by Jay Che’le. Happy reading!

I Manmadúlalak

Tinige’ as Jay Che’le

Nina’lágasgas as tun Boh & i Mangákalukai

På’go na ha’åni hu måtka sientu dihas guini gi lanchu. Annai ma tågo yu’ ni dos saina-hu para bei hanao mågi ya bai ayuda i amko’, pine’lo-ku na para bai fatinåsi gue’ ni na’-ña, bai na’o’mak gue’, pat bai tulaika pañåles-ña kada diha. Lao tåya nai manli’e yu’ amko na taotao taiguini as Chå’—hagas ha u’pos sientu åñus na idåt-ña, lao bråbråbu ha’ ya kalálamten kada diha na u na’lå’la’ i lanchu yan i ga’-ña siha.

Gi magåhet, hu sienti na ti ha nisisíta i ayudu-hu, lao ha súsungon ha’ sa’ esta gaige yu’ guini, ya sempri gof guaguan an para bai hånao tåtte guatu gi isla. Yan magåhet, gi tiempo-ku guini, meggaiña ha fa’nå’gue yu’ put åmot kini i tres åñus na mafa’na’gué-ku gi fane’yåkan yó’amte gi isla. Hu ké’faisen gue’ kada diha put i hagas sinissedé-ña yan espesiåtmenti put i tiempo annai madespóponi ha’ i tano’ ni taotao sanhiyong. Sesso’ umadingan put i hagas gubietnu yan i tiningo’-ña, lao ti malago’ gue’ sumangåni yu’ put i Geran Mananíti Siha. Kada hu faisen gue, ha tulaika i kumbetsasión para otru na kuentos1.

Ya på’go, gi annai munhåyan ham ngumáyu ya esta ha totnge i guafi, hu chagi ta’lu: “Håfa na ma sångan na difirente i tiempun åntes, kao magåhet na manmumu hamyu yan i mangga’chóng-ta ni mananiti siha?” Lao tåya’ ta’lu ineppe’-ña; ha huchom i hetnon lulok ya matå’chong gi siyan machukan para u é’minaipe2 gi fi’on i guafi.

“… Kao un tungo’ sa’ håfa na ma ålok na mandífferent ayu siha na tiempu?,” ha faisen yu’, lao ti ha nangga i ineppe’-ku. “Un tungo’ ha’, noh? Sa’ guihi na tiempu tátaigue’ hao ha’, lao mo’na gi tiempu sempri para un gaige.” Dumíkiki i atadók-ña annai chumålek si Chå’, ya chákka’ka’ i chalek-ña an guiya numa’chålek gue’.

Ti hu gof kumprendi i sinangån-ña lao ti ha sienti—ha kontinuha:

“Åhe’ guåña3, magåhet na manákontra ham guihi na tiempu. Hoben ha’ yu’ guenao na finaisén-mu, trenta sino kuarenta años ha’ na idåt annai matutuhon i mimu, i tinitúhon i finakpo’ i umenimigó’-ta yan siha.”

Esta yå! Tres dihas di hu ke’laknos ini na estoria. Hu gagao na u nanggañaihon ya malågu yu’ para i kusina; mama’tinas yu’ pinakpak ma’es4 pues umåsson yu’ fi’on addeng-ña si Chå’—benti dos åñus yu’ lao kalang påtgon ha’ yu’ umékungok estoria. Ha tutuhon gue’, ya lumá’ma’lak i bos-ña kada umestória si Chå’:

Sumåsåga yu’ giya Tutuhan guihi na tiempu yan i palo’ na maní’e’yak5. Eståba guihi lokkue si Ta’dok, ya guiya ma fa’esgaihón-hu6 gi tres åñus na tinituhon i mafa’na’gue-ku, ni ma’fa’ná’na’an Inalígao. Un diha gi mina’ singku na sakkan guihi, måttu mandåkdåk taotao håya manggágaggao ayudu nu i chelu-ña. Ilek-ña na kalang guaha muna’atmariáo gue’. Kåsi un simåna esta na mali’e na ha kuentútusin maisa gue’ yan lókkue guaha na kalang manman ha’ i taotao.

“Gi nigap, mamokat gue’ huyong gi tasi, ya tres ham manhúyong para bei in kenne gue’ tåtte gi iya håme,” ilek-ña i taotao, ya esta lálaolao i bós-ña. Ensigidas, humame yan si Ta’dok dumalak gue’ guatu gi sagan-ñiha.

In dalak siha taklaya7 guatu gi lugåt ni mafa’ná’na’an Talaifak. Hagas sengsong guihi, ginen dángkulo’ yan bibu, lao kimasón gi Geran Señot8 ya apmam tiempu ti manna’lu tåtte la’meggai na taotao håya, astaki makpo’ i Geran Englis. Gigun humålom ham gi chalan-ñiha kaskáo9, ha de’on yu’ si Ta’dok ya ilek-ña, “Tres guini mangga’chóchong-ta10, unu mo’na yan dos gi tatte; kalang taotao ti maolek11 matan-ñiha.”

Guaha hu siente, lao trabiha ti siña yu’ manli’e aniti siha. Gi magåhet, guiya esti na sinissedi muná’malago’ yu’ umé’yak manli’e. Ma’esgaihon ham gi chalan pues hållom i gimå-ña i che’lu-ña i taotao.

Annai humållom ham, ha fåfåhna’ i liga ya ha chatfinú’i ham na dos; ha tungo’ ha’ i na’an-måmi ya kontodu i fá’fa’någue siha ni in he’hesgi. Hu kuentusi gue’ ya hu faisen håfa i chini’otña ni lahi, ya para håfa na u kastiga i sutteru. Ha sångan na tåt mandå-ku guihi ya para u konne’ i taotao achokka’ håfa in chagi. Nu esti, mañufa si Ta’dok ya ha gú’ot i dos kannai-ña, ha na’ åhlenken i lahi ya tinémba’ gue’ gi guafak.

Metgot i aniti ya ha ké’ke’hulat si Ta’dok, lao metgotña i dos ga’chóng-ña si Ta’dok—magåhet na put eyu malago’ yu’ na guiya i ga’chong-hu guatu. Ha fata’chungi tiyan-ña i lahi si Ta’dok ya ha klåba gi satge ni dos kannai-ña. Hu chule’ i hánom ya hu po’lu siñåt gi pecho’-ña; hu láknos i låña ya hu palalai’i gi papa’ patås-ña yan gi i ha’i-ña, mentras hu lålaigue i sinangan i maga’fá’fa’nå’guen-måmi.

Mumanengheng i kuåttu, esta in lí’li’e i hinagong-måmi; umésalao i aniti ya humuyong gue’ ginen i pachot i lahi, kalang te’ok na åsu. Ha sufa’ i petta pues humuyong ya dumanña yan i tres ni manlini’e as Ta’dok, ya mama’dångkulon birak. Tinattíyi gue’ as Ta’dok ya ha li’e na humålom gi un måmåtai na trongkun mångga gi me’nan i gima. Lumá’meggai ta’lu i hagón-ña ya mamflores lokkue’ i trongku, lao hu tungo’ ha’ na kumu in setta’ siha, u ta’lu tåtte kontra i taotao.

Put eyu, mañonggi ham hågon niyok yan åfok gi ha’íguas, ya lumålai ham gi uriyan i trongku:

“Mañaina-hu yan mañelu-hu,

Fanggái’asi, fanggái’asi nu siha.

Na’ayao ham ni nina’siñan-miyu

sa’ mannaisinétsot i antin-ñiha.”

In chile’ i guafin-måmi yan hagåssas siha para in na’kimasón i trongku: chómchom i hagón-ña ya cháddek manñila’, mámpos dangkulo’ guihi i guafi. Duru åsu i trongku lao ti ha láknos i asu gi hilo’-ña, na ginen i sanpapa’ gi hale’-ña i trongku. Dispåsiu i humuyóng-ña ya kalang taotao i hechurå-ña, ya gi eyu na siña hu taka’ gue’ i mananíti ni mandanña kalang unu. Hu gotte’ i aga’gå’-ña ya hu hålla huyong ginen i trongku, lao ha domu yu’ ya gumupu para i gima’ bisinu, unu tinattítiyi ni tres.

Umá’gotte ham kannai yan si Ta’dok, in falågu guatu ya duru ham lumålai, in dílalak siha para i kanton i tasi ya tumohgi ham gi inai, ya in pattang siha kontra i tano’. En fin, mañule’ gue’ únai si Ta’dok ya ha na’danña yan i hanom ginen i betså-ña, ha pega hålom gi mahettok i chada mentras lumålai, ya humuyong å’paka na åsu, kalang dångkulu na pulun Utak.

An hu li’e i bidå-ña, ngumaha yu’ ya hu hagongi i asu, pues hu guaifi guatu gi mananíti; hu chátsangan siha na ni ngai’an na para u ta’lu siha mågi. Mandanña i kuåtru ta’lu kumu unu gi te’ok na åsu ya malågu gue’ huyong guatu gi i díkiki na isla gi fi’on tano’-ñiha. Guiya enao i ma fa’na’an Annai na lugåt, ya desdi ayu na ha’åni tåya nai maná’estotba siha i mananíti yan i taotao i lugåt.

Sumuspírus didide’ si Chå’ pues ha saosao unu gi atadok-ña. Meggaiña på’go finaisen-hu para guiya, lao esta hu li’e na ti på’go i tiempu ni para bai é’ineppe siha. Sesso’ ham pumeska yan si nanå-hu, nietan Ta’dok, giya Annai yan i tasi-ña, lao ni’ un biåhi di ha mensiona esti na sinissedi ni’ i mananítin i lugåt.

Kumahulo’ yu’ para bai chuli’i gue’ ni såbanas, pues hu nå’yi ta’lu håyu gi feggon lulok. “Kao malago hao na bai fama’tinas chå, saina-hu?” hu faisen i amko’.

“Hu’u, fan” i ineppe’-ña, pues malingu i maigo’-ña åntes di bolókbok i hanom.

A note regarding the translation: The characters Chå’, Ta’dok, and others are not assigned gender in the Chamorro text. To capture this in the English translation, the English pronoun they will be used to refer to singular subjects in the text below.

The Ones Driven Out

Written by Jay Che’le

Edited by Mr. Ray & the Catalysts

Today I mark one hundred days here at the ranch. When I was ordered by my two parents to go here and help the elder, I supposed that I would make their food for them, I would bathe them, or I would change their diapers every day. But I have never seen an elderly person like Chå’ – they have long passed one hundred years of age, but are still active and move around every day to give life to the ranch and their animals.

In truth, I felt that they didn’t need my help, but they were just enduring it because I am already here, and it’s surely very expensive for me to go back to the island. And honestly, in my time here, they taught me more about medicine than my three years of study at the healer academy on the island. I tried to ask them every day about their past experiences, and especially about the time when the land was still controlled by outsiders. They often spoke about the previous government and their knowledge, but they didn’t want to tell me about the War of Spirits. Every time I asked them, they changed the conversation to another topic.

And now, when we finished gathering firewood and they already started the fire, I tried again: “Why do they say that the time before was different, is it true that you all fought against our friends, the spirits?” But again there was no answer from them; they closed the metal oven and they sat down on the rocking chair to seek out heat next to the fire.

“… Do you know why they say that those times were different?” they asked me, but they did not wait for my reply. “You already know, right? Because at that time, you still weren’t around, but in the future you will surely be there.” When Chå laughed their eyes became small, and their laughter was loud when they were the one making themself laugh.

I didn’t really understand what they said, but they didn’t notice – they continued:

“No, actually, it’s true that we were in opposition to each other that time. I was still young then, in the time you are asking about, just thirty or forty years of age when the fighting started, the start of the end of our enmity with them.”

At last! For three days I had tried to get this story out. I asked for them to wait for a little bit and I ran to the kitchen; I made popcorn then I laid down next to Chå’’s feet – I am twenty years old, but I’m still like a kid when I listen to a story. They started, Chå’’s voice brightened whenever they told a story:

I was staying in Tutuhan at that time with the other learners. Ta’dok was also there, and they were my guide in the three years that were the my studies, which was called “The Search.” One day in the fifth year there, a person from the south came knocking, asking for help for their sibling. They said that it was as though there was something that made them psychotic. It was probably about one week since they were seen talking to themself and also sometimes it was as though the person was just staring blankly.

“Yesterday, they walked out to the ocean, and three of us went out to bring him back to our home,” the person said, and their voice was already quivering. Immediately, Ta’dok and I went together and followed them to their place.

We followed them further south to the place which is called Talaifak. A long time ago there was a village there, it used to be large and lively, but it was burned down in the Spanish War, and for a long time many southerners did not return, until the English War ended. As soon as we entered their gravel road, Ta’dok pinched me and said, “There are three who are accompanying us, one ahead and two behind; their faces seem to be ancestral spirits will ill intent.”

There was something that I felt, but I could not see spirits yet. In truth, it was this experience that made me want to learn to see. We were escorted on the road, then into the house of the person’s sibling.

When we went inside, they were facing the wall and cursing the two of us; they even knew our names, including the teachers we followed. I talked to it and I asked what its injury from the man was, and why the young man would be punished. They said that I had no authority there and it was going to take the man, no matter what we tried. Because of this, Ta’dok lunged and held his two hands, and they made the man stumble, and he was knocked down on the woven mat.

The spirit was strong and it was trying to overpower Ta’dok, but Ta’dok’s two companions were stronger – honestly, that is why I wanted him to be my partner going there. Ta’dok sat on the man’s stomach and they pinned his two hands down to the floor. I took the water and I put the sign/mark on his chest; I took out the oil and I smeared it on the bottom of his feet and on his forehead, while I was chanting the words of our high teacher.

The room became cold, we were already seeing our breath; the spirt shouted and came out from the mouth of the man, like thick smoke. It charged the door then went out and gathered with the three spirits that were seen by Ta’dok. It was followed by Ta’dok and they saw that it went into a dying mango tree in front of the house. Its leaves became more numerous again, and the tree also bloomed, but I already knew that if we let them go, it would go back again against the man.

Because of that, we burned coconut leaf with lime in a coconut shell, and we chanted around the tree:

“My elders and my siblings,

have mercy, have mercy on them.

Lend us your might,

for their spirits are unrepentant.”

We took our fire and dried coconut leaves to set fire to the tree: it’s leaves were numerous, and it lit up quickly, the fire there was very big. The tree smoked heavily, but the smoke did not come out from its top, in fact it was from the bottom of the tree’s roots. Its exit was slow, and it was shaped like a person, and it was that I could reach it the spirits that were gathered together as one. I held its neck and I pulled it out from the tree, but it punched me and it flew to the neighbor’s house, one being followed by the three.

Ta’dok and I held each other’s hands, we ran toward them and we kept on chanting, we chased them to the beach and we stood on the sand, and we blocked them from the land. In the end, Ta’dok took some sand and they mixed it with the water from their pocket, they put it inside an egg shell while they chanted, and white smoke came out, like a big Utak feather.

When I saw what they did, I tilted my head up and I breathed in the smoke, then I blew it out toward the spirits; I cursed them, that they would never come back here. The four gathered again, as one thick smoke and it ran out to the small island next to their land. That’s the one, the place called Annai, and since that day, the spirits and the people of the place have never bothered each other.

Chå’ sighed a little, then they wiped one of their eyes. I had more questions for them now, but I already saw that now was not the time to search for answers. My mother (a granddaughter of Ta’dok) and I often went fishing at Annai and its ocean, but not once did she mention this occurrence nor the spirits of the area.

I got up to bring them the blanket, then I added wood again to the metal stove. “Do you want me to make tea, my elder?” I asked the elder.

“Yes, please,” was their answer, then they drifted off to sleep before the water boiled.

Notes

1 otru na kuentus: Literally another talk, sometimes used mark changing topics in conversation

2 é’minaipe: Literally, this means “to search for heat/warmth.” This is a combination of é- + [-in- + maipe]. In the context of the story, it’s used to convey that Chå is trying to get warm by the fire.

3 Åhe’ guåña: No, actually; No, really; A way of indicating that something was untrue or a joke

4 pinakpak ma’es: This is “popcorn.” Literally, it’s a combination of the root word pakpak, which can mean “explode, pop, burst forth” and må’es, which is “corn.” In this construction, it literally means “exploded corn” or “popped corn.”

5 maní’e’yak: This translates to “learners”, and comes from plural man- + [e’yak + reduplication]. Speakers will often change the first e in e’eyak to be i’eyak.

6 fa’esgaihón-hu: This translates to “the one who was made my guide” and comes from fa’- + esgaihon + -hu.

7 taklaya: This means “further south” (in the context of this story, since we are on Guam). It’s a combination of tak- + lá- + håya.

8 Geran Señot: This is a made-up term, referring to the Spanish War.

9 chalan-ñiha kaskáo: The word chalan kaskao means “gravel road.”

10 mangga’chóchong-ta: This comes from the root word ga’chong, which means “partner, mate, friend” and we get to this word by combining plural man- + ga’chong + -ta. However, in the context of this particular scene, it’s used to refer to the taotaomo’na, or “ancestral spirits” that accompany Ta’dok. In English, when somebody seems to possess a great or superhuman ability, we might say that they “have a friend” to mean that a taotaomo’na is with them.

11 taotao ti maolek: This is a phrase that refers to taotaomo’na (ancestral spirits) with ill-intent.

Copyright Notice

This story is copyright 2024 by Jay Che’le. Do not repost or use this story without permission from the author.